by Sarah Baca

Recently I had a doctor’s appointment, and the doctor was talking about how when he works with patients he gives them lots of information. That information includes exercises to help them manage pain. But getting them to actually do those exercises seems impossible. This sounded like a familiar problem to me. I often think I have the answers to help people with their pain, but when I tell them what to do, they also often ignore me.

As an agile coach, it is my job to influence people over whom I have no direct influence. I cannot force change on anyone. And in fact no one can force change, regardless of your title and your ideas that you can force change.

When making changes, one model I like to consider is Jason Little’s Lean Change Model.

In this model, Insights is the time you spend observing the situation as it currently is. Then you move to Options, where you evaluate cost, value, and impact of each possibility. From this you create a hypothesis to test the expected benefits of that test. Using that hypothesis, you form an Experiment.

Lean Change Model is a nonlinear and feedback-driven model for managing change

An important description is that the Lean Change Model is a nonlinear and feedback-driven model for managing change. This means it’s a tango — one step forward and two steps back. The tango-like process can be hard to remember when you’re in the middle of it, but it’s important to remember that this give and take is to be expected. Don’t be discouraged, just keep dancing!

Let’s break down how we apply each of these three actions within an experiment.

Insights: Listening in the right way

As Esther Derby, the famous agile coach and mentor, recently wrote, “Observing sounds simple. In fact, it is hard work and requires practice and skill.”

We often think we are good listeners just because we shut our mouths.

While that is an important part of listening, it’s not the most important part. Watching language used, looking for patterns, and showing empathy are the required skills for listening that we often forget. When searching for Insights, the most important thing to do is listen but we must listen in the right way.

In order to actively listen, utilize facial expressions and body language to show full attention. Ask clarifying questions that are neutral in language and without judgement. Look at the language that people use as they speak and write. Humans think in stories and metaphors, and the language will give you clues about the stories they are telling.

Let’s say you have an executive who says this project is “off the rails” — what does that language show you? This executive feels that there is one clear path forward, and people are not following this path. I have an image of a train that was going one way but it now overturned and went off the tracks, with debris thrown everywhere. This is different than an executive who says that things are “a mess” — I still see debris everywhere but I do not see one direction that we are missing. With a mess I see bits in all different locations. A mess I see being cleaned up bit by bit, a diverted train I see being righted and put back on the tracks. These two metaphors are similar but they have differences. These differences will tell you a lot about how this person thinks.

We then develop Insights by being curious, asking questions, and helping the people we are helping — the people who want the change — create this Insight.

For example, a common problem that managers have is that they say team members need a “sense of urgency.” When you drill deeper (another metaphor!), the phrase can mean different things. Does it mean that they think the team doesn’t care as much as management does? Do they mean the team could be working harder? Faster? If a team has the right “sense of urgency” then what does that look like? By asking questions we can discover what the real problem is, if it actually is a problem, and discover new Insights.

Options: Getting to the roots of a problem

At this point the people you are helping know they have the power themselves to generate the Insight. Now help them generate some Options, asking: What is the root cause of the challenges they are facing? Dig deep to get below the surface and determine what is going on and what might be some possible solutions.

There are several exercises that you can do as a team to get to the root problem whether that’s the classic Five Whys exercise or a Lean Coffee to have a time-boxed, focused conversation about the problems you are seeing. You can use images such as a tree and start at the top with the problem while moving down the tree to get to the roots at the bottom.

Google is your friend when trying to find fun exercises to explore problems.

Experiments: Building on curiosity

Now that we have some possible solutions, work together to create some Experiments to test them. It is important, just like we all learned in Biology 101, to isolate one variable at a time, run your Experiment, and see what happens. Then you can learn from that and determine your next steps.

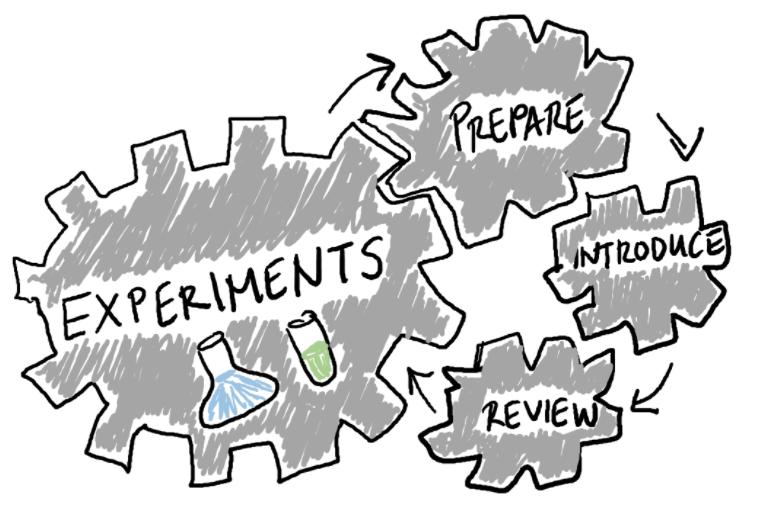

Each experiment includes three parts: Prepare, Introduce, and Review.

Similar to Deming’s Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA), this process has you preparing for the Experiment, introducing the Experiment to those involved, and then reviewing the results together. The key to this is to still use the power of invitation and curiosity — invite team members to participate, get their feedback, and have empathy for their problems. If we don’t have invitation and curiosity that affects the results of the Experiment and might make it so you don’t get helpful results.

In our previous example of a team that has no sense of urgency, let’s say that the root cause you discover is that the team doesn’t understand the big why, the big purpose of what you’re doing. So our experiment might be to have your VP speak to the team and explain how the website you are building will help visitors plan their dream vacation. When the VP speaks, she speaks of the Martinez family who has saved for two years to go on this cruise and how this will be last time Ms. Martinez is with her entire family before Junior goes off to college. We have a graphic artist create a picture of the Martinez family and the events within their dream vacation and we put it up. We talk about it during our meetings and use it as our anchor for every story we tell each other. Does this experiment affect our sense of urgency? Does the work matter more now? How are we measuring this? Let’s check back in a sprint or two and see if we see an effect on those metrics.

By using the Lean Change Model and conducting small Experiments, you can cause transformations in your company or on your team. Try it and share it in the comments below!

My impression is that a lot of things get mixed up in this blog and it is far from reality.

On thing is inquiry like “humble inquiry” proposed by Edgar Schein. An other thing is change management like in “Accelerate” by John Kotter. Still another is scenario planing and hypothesis testing. Process or quality improvement with the famous PDCA-cycle from Edward W. Deming being another aspect. And I thing there was some root cause analysis somewhere as well – I would suggest the five why method used in Lean for that.

No, you cannot change people like that. When it comes to the mentioned “sense of urgency” it means people have to be aware of the difficult situation they are in and that they are willing to change. If there is no “sense of urgency” they rather stick to their old behavior that served them so well in the past.

Conclusion: I’m lost in this blog, there are so many things mixed together that make no sense to me in this combination.